-

1 Introduction

Setting: District Court The Hague, 24 September 2022. Case Birthmothers [‘afstandmoeders’] vs The Dutch State

Plaintiff: ‘Recognition is important, so that everyone knows that it was not our fault that this happened. … I was forced to take this step, to go to civil court.’…

Judge: ‘Would it be possible for you to find recognition outside of the judicial realm?’

Plaintiff: ‘I thought so, yes, it would have been possible, according to me. But not, because the state told me they did not believe it.’

Judge: ‘Did that situation, of the state not believing you, lead you to take this step?’

Plaintiff: ‘Yes’1x Citation (close to literal) and translation on the basis of notes taken by authors from the livestream of the court case of the District Court The Hague on 24 September 2021. See also District Court The Hague, 26 January 2022 (Afstandsmoeders), ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2022:432.Here we are listening to the story of a ‘Birthmother’ (Dutch: afstandsmoeder) as it was told in the Dutch civil court.2x The Dutch word afstandsmoeders reflects the facts that these women had to ‘hand over’ (Dutch: afstand doen van) their children. The word, however, also carries the meaning of ‘distance’ (Dutch: afstand). The English translation cannot do justice to this subtlety and normativity. We use the English translation that is most common in international media coverage of the case. A group of women brought the Dutch state and the Council for Youth Protection to civil court, after, as unmarried mothers, in the 1950s and 1960s they were forced to hand over their children. This legal step has been taken after years of futile efforts to force the state and respective institutions to take responsibility, including unsuccessful talks with the minister. Tort is part of the civil law system, meaning that (contrary the criminal law) it is concerned with the interest of individual parties, rather than the public. This makes tort a seemingly counterintuitive platform to address historical justice. Nevertheless, while other avenues for human rights litigation, like the International Criminal Court, are losing face,3x The International Criminal Court (ICC) is plagued by slowness, disappointing results in light of enormous costs, a striking North-South bias – experienced as ‘colonial violence’ – see Kamari M. Clarke, Affective Justice. The International Criminal Court and the Pan-Africanist Pushback (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2019) – and its Trust Fund for Victims that grants victims the rights to seek and receive reparations has for a long time been chronically underfunded, see Jo-Anne Wemmers, ‘Special Issue on Victim Reparation and the International Criminal Court’, The International Review of Victimology 16/2 (2009). tort litigation for systemic and historical injustice cases is clearly on the rise.4x See Michael R. Marrus, Some Measure of Justice. The Holocaust Era Restitution Campaign of the 1990s (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009); Berber Bevernage, ‘Cleaning Up the Mess of Empire? Evidence, Time and Memory in “Historic Justice” Cases Concerning the Former British Empire (2000-Present)’, Storia della Storiografia/History of Historiography 76/2 (2019); Marc Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?: On Slavery Reparations, Post-Colonial Redress, and the Legitimations of Tort Law’, Journal of European Tort Law 11/3 (2020): 181-207; Caroline Elkins, ‘History on Trial. Mau Mau Reparations and the High Court of Justice’, in Time for Reparations. A Global Perspective, eds. Jacqueline Bhabha et al. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 101-118. In line with the work of Berber Bevernage, historical injustice in the context of civil court litigation is seen to be ‘focused on events that from a legal perspective are considered “historic” or “antique” and which challenge the conventional temporal boundaries of law’.5x Bevernage, ‘Cleaning Up the Mess of Empire?’, 63.

In the last decades, the Netherlands specifically has seen several landmark cases that cover various types of systemic and historical injustice: Dutch military atrocities in Rawagede, Indonesia; pollution and negligence by Royal Dutch Shell in the Niger Delta, Nigeria; failure to prevent genocide in Srebrenica, Bosnia. All these cases have been settled to some extent in the Dutch civil court.6x Cedric Ryngaert, ‘Tort Litigation in Respect of Overseas Violations of Environmental Law Committed by Corporations: Lessons from the Akpan v. Shell Litigation in the Netherlands’, McGill International Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy 8/2 (2012): 245-260; Cedric Ryngaert and Kushtrim Istrefi, ‘Introduction Special Issue “The Legacy of the Mothers of Srebrenica Case”‘, Utrecht Journal of International and European Law 36/2 (2021): 114-117; Larissa van den Herik, ‘Addressing “Colonial Crimes” through Reparations? Adjudicating Dutch Atrocities Committed in Indonesia’, Journal of International Criminal Justice 10/3 (2012): 693-705; Nicole Immler, ‘Human Rights as a Secular Imaginary in the Field of Transitional Justice. The Dutch-Indonesian “Rawagede Case”‘, in Social Imaginaries in a Globalizing World, eds. Hans Alma and Guido Vanheeswijk (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 193-222; Nicole Immler, ‘Colonial history at court: Legal decisions and their dilemmas’, in Time for Reparations. A Global Perspective, eds. Jacqueline Bhabha et al. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 153-167. These are ‘breakthrough’ cases that have spurred societal and media attention. Nor is this momentum for tort as addressing systemic and historical injustice over yet. Although slavery is sorely missing from the above list of ‘breakthrough’ cases – courts have so far ‘been unyielding in their myopic application of the law and understanding of claims for reparations for slavery’7x Makau Mutua, ‘Reparations for Slavery: A Productive Strategy?’, in Time for Reparations. A Global Perspective, eds. Jacqueline Bhabha et al. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 32. – new court cases are now being prepared to seek reparation for Dutch institutions’ complicity in chattel slavery and the slave trade. The question remains: Why tort? Can tort address this form of historical injustice? And what can we learn from earlier systemic and historic justice cases to understand this potential?

Scholars find it difficult to understand the rise of tort law for cases of systemic and historical injustice, distracted by what they see as the sociological and legal limitations of civil law. Exemplary in this respect are the reactions to a landmark decision in the civil court in The Hague in 2011. For the first time, judges held the Dutch state liable for mass executions in Indonesia’s war of independence (1945-1949) and decided that the statute of limitations did not apply.8x The statute of limitations, meant to prevent potential defendants from unfair trials about long-past harm, from which they cannot reasonably be expected to defend themselves – prevents parties from bringing harm to court that has been committed in the far-away past. However, when the plaintiffs can prove that, for example, they were not aware of the harm until a more recent point in time, the statute of limitations does not apply. The specifics of this case will be elaborated on later in this article. While legal scholars like Wouter Veraart embraced it as a ‘milestone’,9x Wouter Veraart, ‘Uitzondering of precedent? De historische dubbelzinnigheid van de Rawagede-uitspraak’, Ars Aequi 4 (2012): 251-259. seeing the importance as a potential ‘catalyst for the Dutch state and society to revisit its colonial past’,10x Van den Herik, ‘Addressing ‘Colonial Crimes’ through Reparations?’, 2. to quote Larissa van den Herik, historians argued that the limited debates on clear defined crimes (‘mass-executions’) would not help to integrate the colonial past into the Dutch master narrative.11x Bart Luttikhuis, ‘Juridisch afgedwongen excuses. Rawagedeh, Zuid-Celebes en de Nederlandse terughoudendheid’, BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 129/4 (2014): 92-105; Chris Lorenz, ‘Can a Criminal Event in the Past Disappear in a Garbage Bin in the Present? Dutch Colonial Memory and Human Rights: The Case of Rawagede’, in Afterlife of Events: Perspectives on Mnemohistory, ed. Marek Tamm (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 219-241. These single disciplinary views have missed out on the resonance of the court cases in the larger socio-political realm, as a potential symbol of a new ‘moral order’.12x Immler, ‘Human Rights as a Secular Imaginary in the Field of Transitional Justice’, 218.

It thus seems hard to appreciate the potential of tort for addressing historical injustice, such as slavery cases, if we are only relying on single academic disciplines, offering only a singular perspective. Legal studies get stuck in tort’s technicalities and, whilst acknowledging its potential, simply conclude that legal venues are a ‘poor fit’ for historical injustice.13x Kaimipomo D. Wenger, ‘Forty Acres and a lawsuit: legal claims for reparations’, Race, Ethnicity and Law. Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance 22 (2017): 89. See also Hanoch Dagan, ‘Restitution and Slavery: On Incomplete Commodification, Intergenerational Justice, and Legal Transition’, Boston University Law Review 84/5 (2004): 1142. On the other hand, the field of transitional justice, focused on the question of how to deal with complex and institutional injustice, tends to argue that the formality and dichotomy of tort cannot account for the historical details, nuances, and complex relationality of historical injustice.14x For more critique on the ability of tort to address historical injustice cases, see Joel Levin, Tort Wars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 124, 126, 136, 153. Since civil law represents individual parties rather than the general interest as criminal law does, many add that tort law may not have the ‘moral heft to handle reparations claims’.15x See Kaimipono D. Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery; or, Why the Master’s Mules Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’, in Injury and Injustice. The Cultural Politics of Harm and Redress, eds. Anne Bloom et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 257-258. Wenger reflects here the conventional thinking on the topic; but he holds that tort law is equipped and capable of dealing with such large cases of harm – and strongly endorses the use of tort and other justice avenues for historical injustice cases (at 256). In this respect, tort might seem to be a hopeless vessel for the aspiration of the slavery justice movement.

This article aims to show just the opposite, arguing that tort can potentially address historical injustices, including slavery. This stems from an empirical observation: in a number of systemic and historical injustice cases – like the aforementioned Rawagede, Srebrenica, Shell, and Birthmother cases – plaintiffs and their lawyers have in fact found a way to, at least partially, overcome the aforementioned academic obstacles. This article asks how to theoretically understand the apparent rise of the practice of addressing systemic and historical injustice cases in tort – and in so doing, to better grasp what potential tort may hold for the slavery justice movement.

With the help of a theoretical framework constructed from socio-legal and transitional justice insights, this article uses an interdisciplinary approach to seek ‘talking points’ between legal understandings of tort and the field of transitional justice that is specialised in historical injustice. This convergence is found within two particular theories from both disciplines: civil recourse theory of tort on the one hand, and transformative justice on the other. Both centre around ideas of agency and participation as key components of the justice process.

What transformative justice is to transitional justice, civil recourse theory is to tort: both expand the scope of what justice can do. While the article starts by re-centering plaintiffs’ agency and participation of plaintiffs in systemic and historical injustice cases, it expands its argument to include ways of re-thinking the agency and participation of lawyers and judges. It is their deep understanding and practice of the law that can lead them to grasp and advance the potential tort holds for the slavery justice movement – an aspiration that is already being expressed by the slavery justice movement itself. This theoretical integration of the ‘talking points’ shared by civil recourse and transformative justice theory leads us to identify five ‘building blocks’ through which tort can be compatible in remedying the historical injustice of slavery.

This theoretical exploration is illustrated with observations from various recent tort cases in the Netherlands, including the aforementioned Rawagede, Shell, Birthmothers, and Srebrenica cases. These cover various types of systemic and historical injustice and thus show that while tort may be a counterintuitive vessel for addressing such injustice, it is in fact functioning as one such vessel already. By analysing what is already happening in the civil court, and imagining what could happen in the future, this article responds to the aspiration of addressing in particular the historical injustice of slavery through tort. This article also calls for judges and lawyers to explore this space for justice more fully.

-

2 Theoretical Framework: The Social Positioning of Civil Courts via-à-vis Historical Injustice

The proposed theoretical framework aims to understand how civil courts are socially situated vis-à-vis addressing historical injustices, with the aim of exploring their compatibility. The fields of socio-legal studies and transitional justice both offer answers to this question. Socio-legal studies allow us to conceptualise courts as societal platforms within a wider societal debate. Transitional justice scholarship gives us an entry into how courts operate within a certain political reality of historically unequal networks and hierarchies. However, the two disciplines use a different language to do so and are often not read together. The proposed theoretical framework combines both literatures to conceptualise four elements of the social positioning of civil court vis-à-vis historical injustices: norms, the spectrum of justice and remedies, relations and responsibilities, and power (im)balances.

Law is often celebrated in our everyday conversation for its supposed neutrality and independency. While these are important qualities of the law, it clearly also is a social, contextual, value-, and perspective-based phenomenon.16x Sally E. Merry, ‘Foreword’, in Mark Goodale, Anthropology and Law. A Critical Introduction (New York: New York University Press, 2017), ix-xv at xii; Carl Auerbach, ‘Legal Tasks for the Sociologist’, Law & Society Review 1/1 (1966): 96. Law ‘embod[ies] societal ideals’ of the world we want to live in.17x Richard L. Abel, ‘Law and Society: Project and Practice’, Annual Review of Law and Social Science 6 (2010): 19. Law can be seen as just another ‘dimension of culture’ that contains formal and informal ‘local knowledge’,18x Michael McCann, David M. Engel and Anne Bloom, ‘Introduction’, in Injury and Injustice. The Cultural Politics of Harm and Redress, eds. Anne Bloom et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 1. both at a state level and reaching beyond the state. Judges do not exclusively define liability through ‘neutral judgement or objective facts’,19x Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery’, 260. but also through ‘learned cultural scripts’, which they themselves may, or may not, be aware of.20x McCann, Engel and Bloom, ‘Introduction’, 8, 12. This article explicitly analyses how these scripts and norms are being negotiated in relation to historical injustice, defining what is just in a social context, in the past and present. Law and rights have the potential to make the contours of a just society visible: they ‘express the “is” and the “ought” of social life’ and they ‘provide a language to name the unfairness and cruelty associated with injuries in society and to begin to imagine solutions’.21x McCann, Engel and Bloom, ‘Introduction’, 1, 22.

Although the formal façade of a civil court case often hides these normative negotiations and considerations, we know from transitional justice that this function of law becomes even more pronounced when systemic and/or historical injustice like slavery are at stake. Law, in this instance, does not only offer a concrete pathway to seek justice, but it also embodies hope about an outcome of fairness and equality.22x Martha Minow, ‘Forgiveness, Law, and Justice’, Calif. L. Rev. 103 (2015): 1619. Critical transitional justice literature offers multiple illustrations of how the socio-legal concept of ‘law in action’ works in practice, beyond conventional borders. Interactions and negotiations together define what law ‘effectively is at a particular time and location’.23x Janine Ubink and Sindiso Mnisi, ‘Courting Custom. Regulating Access to Justice in Rural South Africa and Malawi’, Law & Society Review 51/4 (2017): 830. This is reflected in evolved (restorative) justice practices like the Gacaca Courts in Rwanda, the hybrid court in Cambodia, or innovative remedies by the Inter American Court of Human Rights. While not perfect, they testify to the willingness to look beyond conventional national and international legal procedures. Even though tort is bound to different and very specific legal rules, the case studies proposed in this article are lodged within this broader field of more hybrid and cross-border litigation of systemic and historical injustice.

This article also specifically investigates how judges in tort negotiate these norms in relation to remedy.24x Tsachi Keren-Paz, Torts, Egalitarianism and Distributive Justice (Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007), 17. Legal theorists have recently come to (re)appreciate the reach of tort’s remedies.25x As compared with instrumentalist and economic readings of tort law that were dominant up until recently. Tort does not only serve corrective justice, but has distributive,26x Anita Bernstein, ‘Distributive Justice through Tort (and Why Sociolegal Scholars Should Care)’, Law & Social Inquiry 35/4 (2010): 1099-1135; Keren-Paz, Torts, Egalitarianism and Distributive Justice. punitive,27x Benjamin Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, Georgetown Law Journal 91/3 (2003): 695-756. reparative, restorative,28x Alberto Pino-Emhart, ‘Apologies and Damages: The Moral Demands of Tort Law as a Reparative Mechanism’, (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2015); Rahul Kumar, ‘Why Reparations?’, in Philosophical Foundations of the Law of Torts, ed. John Oberdiek (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 193-213. and symbolic29x Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’; Pino-Emhart, ‘Apologies and Damages’; Keren-Paz, Torts, Egalitarianism and Distributive Justice, 17. functions. The range of these dimensions does not represent mere extremes or outliers of tort law, but concerns its very essence.30x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’. Especially in comparison to criminal law, tort offers both ‘greater flexibility’ and a wide range of civil sanctions.31x Arie Freiberg and Pat O’Malley, ‘State Intervention and the Civil Offense’, Law & Society Review 18/3 (1984): 388. The above conclusions follow from the study of ‘ordinary’ tort cases. In historical injustice cases, the range of these remedies is only broadened. Even though lawyers and judges might themselves be reluctant to put this repertoire into practice, this article investigates these choices in relation to what we know already exists as a possibility.

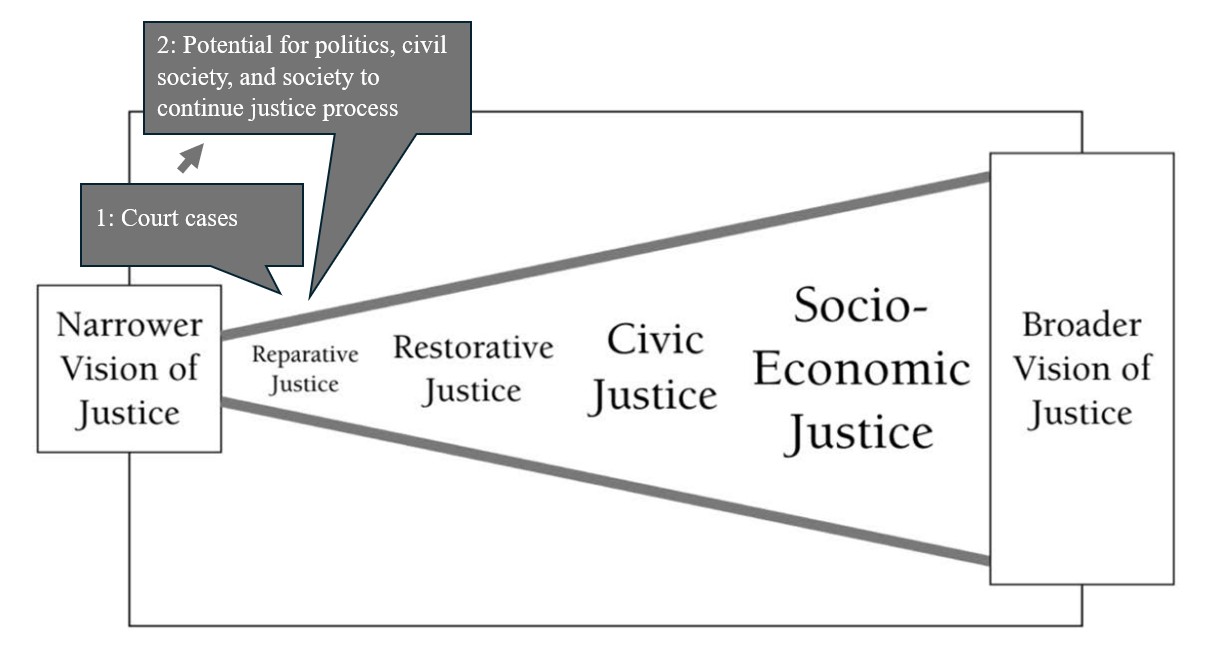

This sensitivity to the potential significance of tort also helps us position the court case within the wider search for justice. Lawyer Lisa Laplante uses the form of a ‘scale’ on which one can move from reparative through restorative to civil and socio-economic justice.32x Lisa Laplante, ‘Just Repair’, Cornell International Law Journal 48/3 (2015): 513.

Cornell International Law Journal © Laplante (with additions Mustafić and Wentholt, forthcoming).

This so-called ‘continuum justice model’ is particularly relevant for cases of historical injustice that are being addressed in tort law, as it allows us to see that doing justice also means finding remedy for the long-term impact of the initial injustice at the level of political, social, and societal relations. The injustice of slavery, specifically, asks far more than reparative justice: it demands that we re-design civic and socio-economic structures. Applying Laplante’s model to the slavery justice debate in the Netherlands has shown that the current reparation claims in Afro-Caribbean and Surinamese communities are about ‘social repair’ and the transformation of social, economic and political relationships to address ongoing structural injustices.33x Nicole Immler, ‘What is Meant by “Repair” when Claiming Reparations for Colonial Wrongs? Transformative Justice for the Dutch Slavery Past’, Slaveries & Post-Slaveries 5 (2025), 22. A civil court case could be expected to directly contribute to reparative justice only, as the other types of justice demand many more societal actors, but it can stimulate these processes towards the right of the spectrum. In the Srebrenica court case for example, the fact-finding and legal conclusions on state conduct provided by the court, had the potential to foster a much wider societal debate on both responsibility and more just relations.34x Alma Mustafić and Niké Wentholt, ‘Finding the Facts but Ending the Conversation?’, Netherlands Yearbook of International Law (forthcoming).

It is this potential for transformation of relations that can follow from a civil court case. In private law, rights ‘are [always] relational and all reasoning about them reflects and preserves their relational nature’.35x Arthur Ripstein, ‘Civil Recourse and Separation of Wrongs and Remedies’, Florida State University Law Review 39/1 (2011): 171. Courts and court decisions ‘inevitably affect human relationships’, not in the least through the emotions they invoke.36x Minow, ‘Forgiveness, Law, and Justice’, 1627. This impact is not difficult to imagine when dealing with the injustice of slavery. Court cases would directly play out and inform conversations that are also being held at kitchen tables, in office canteens, and in parliamentary sessions, and thus have the potential to address – and under certain conditions transform – interpersonal relationships between those that engage: in the court, at home, at work, and in politics. The (partial) restoration of civic relations, on the right side of the aforementioned model by Laplante, is a particularly powerful potential outcome.

The hegemony and inequality associated with courts, however, may make the above seem an overly naïve ambition. Law ‘encod[es] asymmetrical power relationships’.37x Goodale, Anthropology and Law, 22. At the same time, both fields hold that this does not need to impede victim agency and emancipation a priori, stating that law can in fact also be a ‘mechanism for exercising individual and collective agency – often with emancipatory consequences’.38x Goodale, Anthropology and Law, 22. Especially in historical injustice cases, this question of power gets to the very core of the limits as well as the potential of tort – raising a seeming paradox. How can law both embody hegemonic notions of the nation state, perhaps even making it a ‘master’s tool’,39x Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery’. and also be used ‘as a way of bringing attention to […] injustices committed in the past by state representatives’ themselves?40x Stiina Löytömäki, ‘The Law and Collective Memory of Colonialism: France and the Case of “belated” Transitional Justice’, International Journal of Transitional Justice 7/2 (2013): 221.

The practice of court cases shows a way out of this theoretical dilemma. Marginalised groups have for decades criticised the exclusive and biased norms embodied by law. At the same time they have used this very same law for practicing resistance, utilising its formal and authoritative status.41x Mari Matsuda, ‘Looking to the Bottom: Critical Legal Studies and Reparations’, Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 1 (1987): 324-397; Goodale, Anthropology and Law; Merry, ‘Foreword’. The colonial implicatedness of our law system is both an undeniable part of the injustice itself but also a given that has not stopped slavery descendants from using it. Consequently, this article sees the legal arena according to the view of Yamit Gutman, as a ‘discursive public area in which different interpretations of the past express and shape the historical understanding of different groups in society, including majority and elite groups as well as minority and marginalized groups’.42x Yifat Gutman, ‘Memory Laws: An Escalation in Minority Exclusion or a Testimony to the Limits of State Power?’, Law and Society Review 50/3 (2016): 578; see also Löytömäki, ‘The Law and Collective Memory of Colonialism’. Tort can do more than ‘fix’ individual restoration. It has also an undeniable collective element, where the court both represents power and at the same time provides a space to challenge our ideas of power.43x McCann, Engel and Bloom, ‘Introduction’, 15; Jonathan Goldberg-Hiller, ‘Conclusion’, in Injury and Injustice. The Cultural Politics of Harm and Redress, eds. Anne Bloom et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 365-366. Although McCann et al. and Goldberg-Hiller speak specifically of injury here, their insights can be transferred to tort as a whole.

-

3 Civil Recourse Theory and Transformative Justice in Conversation: Addressing Historical Injustice in Tort

The above theoretical framework has shown that tort, perhaps even more so than any other form of law, reflects but also shapes societal norms; holds a comprehensive spectrum of justice and remedies; redefines relations and responsibilities between parties and the broader society; and poses power hierarchies as well as offering opportunities to challenge them. These conceptual characteristics together explain why tort, despite its obvious limitations, embodies a very real aspiration for the slavery justice movement. To understand how this compatibility between tort and justice for slavery would more specifically work, this article combines two theories from the sociological and legal discipline: transformative justice and civil recourse theory respectively.

First, the theory of transformative justice is particularly well suited to deal with the complexities of historical injustice. Developed as a reaction to the field of transitional justice to counter the latter’s tendencies towards affirmative and top-down rather than radical change, transformative justice essentially aims for empowerment of those affected by historical injustice in the justice process itself. It aims to transform the root causes that have created the initial injustice in the first place, in an open-ended process that leads then to a more just society. It emphasises agency and participation as being core characteristics of this process.44x Paul Gready and Simon Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice: A New Agenda for Practice’, International Journal of Transitional Justice 8/3 (2014): 339-361.

Second, civil recourse theory pivots around concepts such as agency and participation. It departs from the idea of a plaintiffs’ ‘right of action’ rather than reframing it as a ‘right to response’ that is so central to tort: the ‘principle that the plaintiff is entitled to act against one who has legally wronged him or her’.45x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, 735. This differs from the dominant view of tort law as being corrective justice as it puts tort’s goal not simply correcting loss ‘for correction’s sake’ but as ‘a mechanism for reasserting the relational equality between the injurer and the injured’.46x Cristina Carmody Tilley, ‘Tort Law Inside Out’, The Yale Law Journal 126/5 (2017): 1330. Civil recourse offers a ‘relational account of tort’47x Stephen Darwall and Julian Darwall, ‘Civil Recourse as Mutual Accountability’, Morality, Authority, and Law 39/1 (2013): 29. in which plaintiff and defendant are ‘relationally situated’.48x Tilley, ‘Tort Law Inside Out’, 1334.

Transformative justice and civil recourse theory thus share two conceptual common denominators: first, agency through process, and, second, participation through inclusion. The analysis of each results in five specific building blocks through which tort could be compatible with addressing historical injustice: 1) right of action: centering plaintiffs as key actors; 2) diligent care: setting norms for just behaviour; 3) legal norms in social context: defining what is right and wrong; 4) statute of limitations: drawing and erasing lines in time; and 5) reparations: redefining state-citizens relations.

Specific examples from the aforementioned landmark cases of systemic and historical injustice illustrate these theorised building blocks in practice. Together, the theoretical explorations and illustrations reflected through the practice itself will show the potential of tort cases for addressing historical injustices, such as the one championed by the slavery justice movement. This analysis can also be read as a call on plaintiffs, lawyers, and judges to explore their full capacity in addressing historical injustice in court – including the injustice of slavery.

3.1 Agency Through Process

Transformative justice criticises conventional (transitional) justice mechanisms for objectifying victim-survivors and locking them into the role of performers, ‘offer[ing] them little or no agency in challenging power relations’.49x Gready and Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice’, 357. The challenge of transformative justice is to (re)frame and position victim-survivors as being ‘agents rather than objects of intervention’, developing ‘civic competence’: ‘the ability to sustainably champion justice and contest marginalization, thereby challenging narrow, exclusive notions of victimhood’.50x Madlingozi, cited in Gready and Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice’, 359. This agency deserves increased importance in the understanding of justice not only as an outcome, but also as a process.51x Gready and Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice’, 357.

The position of civil recourse theory on tort seems to match well with this ambition of transformative justice: it claims that victim-survivors can build agency through tort itself as a process. Civil courts, as Zipursky writes, ‘empower individuals to obtain an avenue of recourse’.52x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, 755. As they turn to the civil court room, plaintiffs take several steps that all hold emancipatory potential. They need to identify that they have suffered a wrong, to identify who has done them wrong, and to find the vessels or channels to pursue justice. Transformative justice and civil recourse theory together thus ask us to zoom into the procedural character of civil court cases and hence the potential for victims’ agency, which manifests itself in two building blocks that will be explained in full below: offering plaintiffs the right of action, and establishing the norm of diligent care.

3.2 Building Block 1. Right of Action: Centering Plaintiffs as Key Actors

Court rooms, with all their rules and limitations might seem to overshadow all participating parties. But within the court room itself, victim-survivors, in the role of plaintiffs, take on a pivotal role in tort. This forms the basis of the civil law system that civil recourse theory highlights. It is what sets private law apart. ‘If the victim is satisfied, then all other matters of justice can be suppressed’.53x Levin, Tort Wars, 30. In public law, in contrast, considerations of deterrence, retribution, and even political nature may all determine the court’s outcomes.54x Levin, Tort Wars, 29-30. ‘The rules of tort law (…) give victims power’, albeit a restricted form of power that is dependent on the wrong that has been committed.55x Curtis Bridgeman, ‘Civil Recourse or Civil Powers?’, Florida State University Law Review 39/1 (2011): 11.

The centrality of agency leads civil recourse theory to move away from the notion of there being a duty to repair, so central to conventional corrective justice theory on tort. The procedural context is key here where, according to Zipursky, the duty to repair is not really a duty that is presupposed but instead, it is enforced. A duty to repair thus only has meaning once it is activated, meaning that we should shift our attention to who actually enforces this: the plaintiff. Civil courts are required ‘to respond to demands by plaintiffs’.56x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, 733. The state offers plaintiffs a ‘right of action’ against the entity that committed injustice; there is no pre-existing duty to repair as the state needs the plaintiff to present a case.57x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, 699. Here we do not rule out the possibility that this view on wrongs, right of action, and the range of remedies can be covered through an extensive understanding of corrective justice theory as well, as is for example argued by Arthur Ripstein. However, the term of civil recourse is particularly apt here to highlight the agency of the plaintiff, which is a concept shared by Ripstein and other defendants of corrective justice theory. Since a tort case requires agency from both plaintiff (who needs to go to court) and the judge (who needs to respond to this right of action),58x In addition to the above footnote, this is a thought that is shared by some proponents of corrective justice, too. They may agree that tort is defined by the agency of the ‘right holder’ to decide whether or not she or he wants to see the wrong pursued in court and thus exercise their right. See Ripstein, ‘Civil Recourse and Separation of Wrongs and Remedies’, 200. this article considers the plaintiffs’ and the judges’ agency in tandem. We learn more by shifting our attention away from this institution-centered notion and our focus which is on those who do the activating: the plaintiffs who have the right of action.

The central position of the plaintiff becomes all the clearer when compared to the position of the victim in criminal law. Not only can the prosecutor decide not to go to trial in the latter case, in civil law victim-survivors’ claims are also central to the judge’s decision.59x Liesbeth Zegveld, Civielrechtelijke verjaring van internationale misdrijven (Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam, 2015), 16. In the Srebrenica case the judge was not necessarily interested in the intention of the Dutch military, but in its ability to act differently, as put forward by the plaintiffs, on the basis of the knowledge at the time.60x Mustafić and Wentholt ‘Finding the Facts but Ending the Conversation?’ (forthcoming). Because intent does not need to be established, ‘the burden of proof in a civil case is considerably lower’.61x Zegveld, Civielrechtelijke verjaring van internationale misdrijven, 13. This is especially useful in cases of historical injustice when the lines of responsibility may be blurred, such as in the case of slavery, but where the harm is directly visible and tangible, and where it must be addressed. Instead of seeking intent, the judge can thus focus on examining and applying social norms of the harm and of the political and societal responsibility. This offers plaintiffs and their lawyers the opportunity to question these norms. Moreover, the plaintiffs can foreground other norms that are also in line with their ideas of just remedy and of a just society.

In the Rawagede case, for example, those who were excluded at the onset – the children of those murdered who were considered to be only ‘descendants’ and as such ‘less affected’62x District Court The Hague, 14 September 2011 (Rawagedeh), ECLI:NL:RBSGR:2011:BS8793. – rioted in the village as they felt overlooked. They then filed their own claim demanding equal treatment.63x Immler, ‘Colonial history at court’, 157. Plaintiffs thus hold agency until well after tort litigation. Furthermore, when compensation is granted, they can also negotiate or reject the amounts determined by a commission. One year after the Supreme Court’s verdict, the Mothers of Srebrenica rejected the first proposal for compensation. They also publicly expressed their dismay about what they felt to be both an overly technical interpretation of responsibility by the Dutch state, as well as the compensation process that was lacking.64x Mustafić and Wentholt ‘Finding the Facts but Ending the Conversation?’ (forthcoming). This remained in vain as no alterative was put forward. But even when taking on a seemingly accepting stance, plaintiffs can (re)take a certain moral and civic position, especially if there is a similar willingness on the side of the defendant. Those directly affected, but also their indirect representatives ‘can accept offers of reparations in the spirit intended and with grace, likewise signaling that they are willing to extend trust to those making a sincere effort to create a scheme of just cooperation’.65x Leif Wenar, ‘Reparations for the Future’, Journal of Social Philosophy 37/3 (2006): 404-405.

For the slavery justice movement, this is highly significant as it means that descendants can make use of this agency as plaintiffs well before the start of the official court case. Together with their lawyers, they can make strategic choices to formulate their claims so that the judges discuss the most relevant norms and put forward viable alternatives. The next section will look into the potential of re-negotiating ideas of what was and is just behaviour through the norm of diligent care.

3.3 Building Block 2. Diligent Care: Setting Norms for Just Behaviour

The presumed neutrality of the law is easy to mistake for a straightforward application of pre-ordained legal rules. During the judicial process, as the theoretical framework has also set out, plaintiffs, lawyers, and judges do negotiate and apply societal norms, especially in their formulation and application of diligent care (Dutch: zorgvuldigheidsnorm). This is a key norm in Dutch civil law that covers an action (or the lack of it) that violates the societal perception of normal and just behaviour.66x Elizabeth van Schilfgaarde, ‘Negligence Under the Netherlands Civil Code: An Economic Analysis’, California Western International Law Journal 21/2 (1991): 273. This norm is fluid and requires the judge to make the connection between different layers of norms, both legal and societal. Especially in systemic and historical injustice cases, the judge’s interpretation of diligent care brings together national legal understandings as well as international law, agreements, and conventions. This legal pluralism ‘provides justice seekers with a choice of normative systems’,67x Ubink and Mnisi, ‘Courting Custom’, 830. whilst at the same time allowing judges themselves a way in which to turn to regional, national, or international norms. In the case of military harm, for example, the norm of diligent care is regularly assessed according to the European Convention on Human Rights.68x Emilia Steendam Visser, ‘De Nederlandse luchtaanval in Hawija: enkele handvatten ter beoordeling van de onrechtmatigheid’, Overheid en Aansprakelijkheid 19/2 (2021): 52.

In applying diligent care, the judge could be said to be more concerned with society and the plaintiff than with the defendant as diligent care does not presuppose morality on the side of the defendant, or even the capacity for moral judgment.69x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, 727. Instead, the judge might depart from what is considered to be fair behaviour on the basis of shared societal norms, even if the defendants themselves feel that those norms do not apply. In the case of Milieudefensie v. Shell, for example, the plaintiffs successfully argued that the human rights frame should be applied as the basis for diligent care.70x District Court The Hague, 26 May 2021 (Climate case against Shell), ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339, at 4.5.4.

Especially with the current societal attention on the slavery past, in the civil court room descendants can carefully lay out their perspective on the norms that slavery violated, and thus advance the societal conversation on what is just – and what could potentially transform societal relations. This, as the next section will elaborate, allows them to carefully approach conversations on accountability too, and thus re-imagine the relation between the past and present.

3.4 Participation Through Inclusion

As a central concept of transformative justice, participation can ‘become a key element of empowerment that sees the marginalized challenge, access and shape institutes and structures from which they were previously excluded’.71x Gready and Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice’, 358. This may eventually lead to a ‘a form of participation that engages and transforms victimhood’.72x Gready and Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice’, 358. Gready and Robins emphasise that acknowledging disagreement and power asymmetries is central to transformative justice. Participation in justice processes – beyond just legal proceedings – must take into account the ‘politics of location’ as well as those of time. It must put the loci of ‘rights talk’ on both the communities where the violations occur(ed), going beyond the ‘metropolis and official spaces’ and acknowledge the overlap and politics of ‘local and national histories’.73x Gready and Robins, ‘From Transitional to Transformative Justice’, 358-359.

This focus on relationality, in terms of defendants’ accountability towards plaintiffs, as well as the connection between those two parties and whom they represent (the state, citizens) and the overall community, is central to the civil recourse theory of tort too.74x Darwall and Darwall, ‘Civil Recourse as Mutual Accountability’. According to Darwall and Darwall, the relationality of tort as well as the acknowledgement of plaintiffs’ individual authority in their right of action leads to the notion of ‘mutual accountability’. Interestingly, even those opposing the need for a separate relational civil recourse theory do so on the basis that also in private law, rights ‘are [always] relational and all reasoning about them reflects and preserves their relational nature’. Ripstein, ‘Civil Recourse and Separation of Wrongs and Remedies’, 171. For the slavery justice movement, this means that tort can offer a platform for challenging power relations. What are the ‘building blocks’ in the tort process whereby plaintiffs and their lawyers might find these opportunities for participation through inclusion, and how might judges respond to them, potentially resulting in accountability and transformation of power relations? This section will discuss three of such building blocks: defining legal norms in a social context, applying or foregoing the statute of limitations, and ordering reparations to redefine community relationships.

3.5 Building Block 3. Legal Norms in a Social Context: Deciding What Is Right and Wrong

Historical injustice cases confront our tort system with the challenge of establishing continuity and discontinuity of what is right and wrong over time. When a long period of time has passed between the occurrence of the wrong and the trial, the judge needs to spend considerable effort establishing continuity between the parties involved. In addition, there needs to be symmetry between wrongdoing and remedy as ‘two sides of the same coin’.75x Marc Loth, ‘Is Tort Law a Remedy for Historical Injustice? On Post-Colonial Redress, Slavery Reparations, and the Legitimations of Tort Law’ (2019), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3491666, 16; Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’, 186. Thus, the decision about what would make right in the present directly speaks to the legal interpretation of what went wrong in the past. Establishing liability, requires ‘multiple kinds of attenuated causation’ that are difficult for a judge to deal with, even more so in the context of the ‘unique harms of slavery’.76x Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery’, 257.

Wrongdoer and victim are thus both contested categories in historical injustice cases, being (re)defined during the process of tort itself. Seeing legal rules as a partial extension of societal norms, allows us to understand that when parties in tort define the wrong, they are transcending the present as they construct a potentially powerful narrative on what is considered to be just in a social context. Tort law departs from the basic assumption that a community shares ideas of what is right and wrong.77x Tilley, ‘Tort Law Inside Out’, 1345. To establish whether the act was a wrong requires active effort from the judge in (re)defining the social and normative context.78x Bridgeman, ‘Civil Recourse or Civil Powers?’, 12; Ripstein, ‘Civil Recourse and Separation of Wrongs and Remedies’, 195. In contrast to criminal law, liability in civil law does not need to be exclusively individual and can include unintended and indirect harm.79x Freiberg and O’Malley, ‘State Intervention and the Civil Offense’, 383. This allows for a wide range of historic harm and thus of remedy options to be discussed through tort law.

Coming back to the context of the slavery justice movement, we see how a tort case on slavery could thus show the need for a broader conversation in society on this web of relations in history and in the present day, allowing for new insights into questions of responsibility and reparation. After all, the judge does not only rule on what is normal for the individual parties, or even for that moment, but for society as a whole; in past, current and future times. In the Rawagade case the Court ruled that the act was wrongful according to the prevailing standards of the time and not only those in the present.80x Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’, 203. Hence, in contrast to criminal law, civil law offers the possibility of retroactive liability.81x Freiberg and O’Malley, ‘State Intervention and the Civil Offense’, 385. The judge is able thus to establish a moral continuity between past and present.

In proposing or establishing this moral continuity between the then and the now, plaintiffs, lawyers, and judges can respond to societal changes. Tort is agile ‘in keeping pace with change, be it moral, economic, or technological’.82x Tilley, ‘Tort Law Inside Out’, 1355. In this reading, tort law does not only go beyond individual choices and particular moments: it also goes beyond the legal and enters the realm of the moral. A civilian right then becomes much more than an individual plaintiff’s choice, but a moral right. Civil recourse theory holds that civilians’ right of action constitutes a ‘prelegal moral entitlement’, corresponding to ‘prelegal moral rights and duties’.83x Bridgeman, ‘Civil Recourse or Civil Powers?’, 14. Given the current attention for the slavery past and the abundance of ensuing research into state and institutional involvement, the parties in tort may allow these societal insights to enter their legal conversation. This applies to the claims being made by plaintiffs and lawyers, but also to the decision-making of judges. A judge applies existing norms or even sets new ones and sends respective signals to the society.

3.6 Building Block 4. Statute of Limitations: Drawing and Erasing Lines in Time

The passage of time is one of the main obstacles in historical injustice cases. The statute of limitations can, intentionally or unintentionally, exercise hegemonic power by deciding that certain harm is not relevant or admissible. Victims of historical injustice cases often seek reparations for the very fact that they are experiencing the harm’s consequences – not in the past, but in the present. Reparation claims, according to legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron, are about ‘ongoing injustice rooted in actions that took place in the past’, as it is only in cases where the injustice has been ‘superseded’ that no action needs to take place; ‘entitlements are sensitive to circumstances’.84x Jeremy Waldron, ‘Superseding Historic Injustice’, Ethics 103/1 (1992): 20. If in cases of historical injustice the judge were to decide that the statute of limitations does not apply, this can carry significant participatory and inclusive meaning.

In this decision, the judge can actively seek rapprochement for the situation experienced by the claimants, often recognising the continuity of the injustice. In the Rawagede case, the District Court ruled, in the words of Marc Loth, that besides constituting an exceptional case with the widows not having had access to the court at the time,85x Loth, ‘Is Tort Law a Remedy for Historical Injustice?’, 5. the case concerned a history ‘that was not yet closed’.86x Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’, 186. The case was compared to established standards such as World War II reparations which are still ongoing, bringing to the fore an awareness of double standards87x Immler, ‘Human Rights as a Secular Imaginary in the Field of Transitional Justice’, 203; Nicole Immler and Stef Scagliola, ‘Seeking justice for the mass execution in Rawagede. Probing the concept of “entangled history” in a postcolonial setting’, Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice 24/4 (2020): 14-15; Liesbeth Zegveld in Jakarta Post (13 September 2013): ‘These cases [such as compensation to Jewish Holocaust survivors] go further back than Rawagede, so how come that no statute of limitation is put upon them?’. – and was thus judged admissible on grounds of ‘equity and reasonableness’.88x Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’, 203; Zegveld, Civielrechtelijke verjaring van internationale misdrijven, 15-16. The factual passage of time becomes just one consideration for the judge in a list of many.89x Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’, 203. In advocating for the statute of limitations to be lifted, plaintiffs and their lawyers can build a case for transforming legal and societal thinking about the very essence of the harm done: they invite society to see it not as something from the past, but as something occurring also in the present.

As part of the same appreciation of lawyer’s agency, it is important to mention here that lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld has been advocating for changing the statute of limitations in such civil cases altogether, based on a similar argument of the judge in the Rawagede case: trial of crimes of this magnitude never come too late. But this requires the legislative power of the state to adjust the law, and it is most likely to result in more cases against the state itself.90x Zegveld, Civielrechtelijke verjaring van internationale misdrijven, 16. Currently, such a political change remains unlikely. While the Rawagede case was a pioneering step in scrutinising the status of limitation for historical injustice, this alleged precedent has not turned out as a blanket case rule: judges in other historical injustice civil court cases have continued to apply the statute of limitations, although plaintiffs’ lawyers in these cases used similar arguments about the enduring harm of ‘past’ injustices. In the foreseeable future, the individual capacity and willingness of the judge to respond to this type of reasoning in their decision to apply or not apply the statute of limitations, remains of high importance.

3.7 Building Block 5. Reparations: Redefining State-citizens Relations

The article has thus far discussed four building blocks with which tort law can potentially bolster agency and participation, both essential terms in transformative justice and civil recourse theory. The question that now remains is whether tort can also offer a fifth building block in which it can transform ‘fractured moral relationships between citizens’ caused by historical injustice.91x Kumar, ‘Why Reparations?’, 198-199. In line with Joel Levin, the challenge is to incorporate tort law within a bigger societal system in which it can be used to solve ‘small conflicts’ as well as bigger conflicts – stemming from historical justice – hence avoiding ‘social wars’.92x Levin, Tort Wars, 8. If the judge decides to grant reparations for historical injustice, even in instances where there is no direct relation between defendant and wrongdoer, Rahul Kumar stresses, it does not necessarily do so because of the past harm, ‘but in order to make things better in the future’.93x Kumar, ‘Why Reparations?’, 199.

This applies to the slavery justice movement too, and is at the core of its message. Alongside acknowledging past harms, about the justice and reparation that is being sought, it is mostly about acknowledging the harm’s legacy, ongoing racism, discrimination and unequal opportunities. The slavery justice movement sees the value of reparations in changing the present and future, which requires more ‘participation in decision-making processes’ that also change the nature of the ‘social relations’ at stake, transforming the unequal power relationships at the basis of the reparation claims.94x Nicole Immler, ‘De doorwerking van het slavernijverleden: een transgenerationeel perspectief op herstel en transformative justice’, in Staat en Slavernij: Een terreinverkenning van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, eds. Rose Mary Allen et al. (Amsterdam: Athenaeum, 2023), 90. In all tort procedures in the US against governments and private companies such as insurance companies, banks, railroads, and newspapers that benefitted enormously from the institution of slavery, the statute of limitations and questions of causality proved fatal legal barriers. Nevertheless, the legal claims had ‘a storytelling and consciousness-raising function’, as Kaimipono D. Wenger states.95x Wenger, ‘Forty Acres and a lawsuit’, 72, 90.

A telling example in this respect is an interlocutory proceeding (kort geding), initiated by Dutch reparation activists against the apology Prime Minister Rutte wanted to issue to the descendants of enslaved people on 19 December 2022.96x District Court The Hague, 23 December 2022, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2022:14035. Several months later, as part of a ceremony on the Netherlands’ National Remembrance Day of Slavery Keti Koti on 1 July, King Willem-Alexander gave a speech apologising for the country’s involvement in the slave trade. On these speeches, see also Wouter Veraart, ‘The Most Salient Legal Hurdle’, 211-226 in this special issue. Some descendants felt sidelined because the date was set without consultation and challenged this top-down decision through an interlocutory proceeding, which they lost. Nevertheless, this small but significant legal intervention pressured politicians to listen to the grassroots and their expectations of what an apology should look like. This case shows that ownership of the process is a crucial part of justice.

The potential of tort is even more meaningful when reparations are at stake. Reparations have the potential to positively impact and even transform social relations. Reparations granted through tort have the ability to ‘remove the hindrances to justice by clearing the ground so that trusting relations can take root’.97x Wenar, ‘Reparations for the Future’, 404. Can tort litigation restore plaintiff-defendant relations even when the defendant is a powerful institution such as the state itself? It is the state, after all, that structures, enables, and regulates this civil recourse. It offers the plaintiff the right of action, or the opportunity to civil recourse. While the judge herself and her rulings function as an independent power in the trias politica division of power, the legal system underlying this power represents the functioning state that is created by society and the state as a whole. The judicial process as a whole represents what the state and the community itself consider as being just. The ‘relational equity’ that stems from these rights is a form of political entitlement.98x Tilley, ‘Tort Law Inside Out’, 1334. Aligned with what can be considered as the social contract, the right of action in tort can be understood as ‘the state’s civil empowerment of individuals who have been wronged against the wrongdoer’.99x Darwall and Darwall, ‘Civil Recourse as Mutual Accountability’. In scholarly debates on civil recourse theory, much attention has been paid to the role of vengeance in defining the difference (or overlap) in civil recourse and corrective justice theory. This is a relevant question to ask from the perspective of the plaintiff, but is less relevant for this article where the focus is primarily on the potential contribution of tort to transformative justice, in which vengeance plays a lesser role. Citizens give up their right to immediate response against wrongdoing, as part of the social contract, in exchange for a legal response to wrongdoing.100x Bridgeman, ‘Civil Recourse or Civil Powers?’, 2.

This focus on relationality and even social contract as a basis for tort, brings to the fore ideas of community in both sociological and political terms.101x Darwall and Darwall, ‘Civil Recourse as Mutual Accountability’. Through enabling tort law, the state encourages civilians to pursue justice and ‘the instinct to hold another accountable’.102x Jason M. Solomon, ‘Equal Accountability Through Tort Law’, Nw. UL Rev. 103 (2009): 1814. In this light, it is interesting to zoom in on the particular standing of the Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad). Already in 1990, Peter van Koppen proposed that the Dutch Supreme Court took on an increasingly political role. However, the rather undisputed and a-political appointment of judges shows that the court is hardly politically contested. According to Van Koppen, this suggests that Dutch politics appreciates the court’s ability to decide on controversial issues because it avoids political conflict over these issues. Peter J. van Koppen, ‘The Dutch Supreme Court and Parliament: Political Decisionmaking versus Nonpolitical Appointments’, Law & Society Review 24/3 (1990): 745-780. This is especially powerful in instances where the state itself is the defendant. The state can then reinstate itself as an executive, trustworthy, perhaps even moral actor through the role of the judge, but especially by accepting its own accountability.103x Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, 722, 747. Ironically, this task befalls tort and is often due to the initial unwillingness of the state to take responsibility. In the Rawagede case, the state’s unwillingness to take responsibility turned a simple recognition claim into a lawsuit,104x Immler and Scagliola, ‘Seeking justice for the mass execution in Rawagede’, 14-15. and, furthermore, a legality that guaranteed that children can take over the lawsuit of their parents.

Where it is held liable, the state can confirm its contribution to reparation by accepting to execute the compensations ordered by the court.105x Specifically in the Netherlands, the state sets itself apart by being the most compliant category of defendants in civil court cases. See Peter J. van Koppen and Marijke Malsch, ‘Defendants and One-Shotters Win after All: Compliance with Court Decisions in Civil Cases’, Law & Society Review 25/4 (1991): 803-820. Of course, this does not necessarily translate into all historical injustice cases. In the words of Kumar, we need to move beyond compensatory or corrective understanding of tort law to see how reparations can be understood as ‘restoration’.106x Kumar, ‘Why Reparations?’, 198. This may happen at the level of individual victims, when recognition of the degrading harm and subsequent reparation can help the ‘recovery of one’s moral personality and the reconfirmation of one’s moral values such as equality and human dignity’.107x Loth, ‘Is Tort Law a Remedy for Historical Injustice?’, 17. It may also extend to groups of citizens and society as a whole. It is reparations that can ‘communicate atonement for past wrong, and thus heal the relationship between the wrongdoers and the wronged’ to ‘restore relations of mutual respect and civic trust’.108x Kumar, ‘Why Reparations?’, 198-99. According to Loth, the Supreme Court rulings on Srebrenica that confirmed that the Dutch state’s liability ‘may have contributed to the process of coming to terms with this horrific event’.109x Loth, ‘Is Tort Law a Remedy for Historical Injustice?’, 17. For all its flaws, legal decisions can incentivise individuals to apologise and ‘invit[e] people to draw upon or develop personal ties and social norms’.110x Minow, ‘Forgiveness, Law, and Justice’, 1626. After the Supreme Court rulings on Srebrenica, the Dutch state eventually formally apologized to the Bosniak survivors. Such an apology has the potential to lead to new, more equal norms and to the repair of the damaged social and civic relationships of the Bosnian-Dutch community.111x Mustafić and Wentholt ‘Finding the Facts but Ending the Conversation?’ (forthcoming).

For slavery, Alfred Brophy adds, tort can play a particularly useful role in ‘framing discussions of moral culpability’. Tort offers ‘important analogies’ of past and current victims and it offers an assessment of the ‘continuing harm’.112x Alfred L. Brophy, ‘Reparations Talk: Reparations for Slavery and the Tort Law Analogy’, BC Third World LJ 24 (2004): 103. Even when it does not result in reparation through money, serving as the ‘embodiment of communal remembrance’ and ‘public recognition’,113x Waldron, ‘Superseding Historic Injustice’, 6-7. tort offers a platform to ‘educate the public about the effects of slavery’.114x Brophy, ‘Reparations Talk’, 103. Thus, tort is not only a potential vessel for transformative justice due to the corrective, restitutive, or reparative remedies it may offer, but also for the knowledge it may help create, highlight, and spread within the wider societal conversation. In the cases of Rawagede, Srebrenica, Birthmothers, and Shell, these were civil court cases that resulted in increased visibility for plaintiffs or even, as was the case for Rawagede: made them visible for the first time to a broad public through media interviews and broadcasts. Tort, with its centrality around plaintiffs and its ability to hold the state accountable, has the potential to set the historical record right. To ‘neglect the historical record’, Jeremy Waldron reminds us, violates ‘identity and thus to the community that it sustains’.115x Waldron, ‘Superseding Historic Injustice’, 6.

Tort can offer this broader form of recognition – as the Rawagede case showed116x Van den Herik, ‘Addressing ‘Colonial Crimes’ through Reparations?’; Immler, ‘Human Rights as a Secular Imaginary in the Field of Transitional Justice’. – and bolster victim communities, as well as help them restore relationships with the wider society. Whether framed as socio-psychological healing, societal satisfaction, or moral reflection, a first step in the repair of social relations through tort constitutes a strong potential for the slavery justice movement. Again, this is not conditional upon a successful legal outcome. Activists have already succeeded in putting the slavery past into the center of public attention. A civil court case can then serve, regardless of the eventual decision of the judge, as a platform to center the story of plaintiffs and propose a vision of justice and reparation that can reach beyond the walls of the court.

-

4 Conclusion: About the Space Tort Offers to Manoeuvre

As lawyer I am mainly interested in the deeper norms and values building the foundation of law. That is why I am not afraid to lose a case. The law is a living instrument, it has to be developed. And that happens only when there are people who appeal to it. Only then changes happen.117x Liesbeth Zegveld, lawyer in several landmark historical injustice cases, in an interview with Josselien Verhoeve, Moesson 2 (August 2016), 29.

This article contributes to our understanding of how, and with which impact, historical injustice cases can be pursued as torts in a civil court. But of course, these theoretical explorations do not automatically translate into reality. One only needs to speak to plaintiffs who have been through this process to know just how tiring and often (re-)injuring such court cases can be, reproducing the initial injustice or producing new forms of harm. Defendants may be unwilling and judges may be unreceptive. Hence, the above should not be read as a case for pursuing historical injustice cases exclusively in tort. The very definition of transformative justice requires a multidimensional approach that includes and even foregrounds non-legal mechanisms. Nonetheless, this article has shown what tort can potentially achieve.

This article is thus a call for legal theorists, lawyers, and judges to take upon themselves the freedom and space tort allows for. As Loth noted in 2019, historical injustice cases offer courts ‘an opportunity to play a role beyond their strictly legal responsibility of deciding cases on their merits,’ but ‘some courts are more willing to play that role than others’.118x Loth, ‘Is Tort Law a Remedy for Historical Injustice?’, 18. To make it even more specific, using the words of Berber Bevernage: there are ‘gate-keeping judges’ who ‘have embraced or rejected the law’s new role in cleaning up the mess of empire’.119x Bevernage, ‘Cleaning Up the Mess of Empire?’, 64. Plaintiffs, often display a clear need for psychological and moral redress through the court rooms, specifically coming from judges for the authority they represent. This article hopefully has offered some reason to explore the role of the court in this regard.

Combining socio-legal and transitional justice scholarship, the theoretical framework conceptualised the social positioning of civil courts vis-à-vis historical injustice through norms, the spectrum of justice and remedies, relations and responsibilities, and power (im)balances. It is within such fluid understandings that the aspirational quality of tort, also appealing to the slavery justice movement, becomes clear. The article analysed the theoretical basis for this potential and aspiration, by identifying the ‘talking points’ between two theories from the sociological and legal discipline: transformative justice and civil recourse. Both theories share a conceptual emphasis on agency through process and participation through inclusion. Within these common concepts we identified five building blocks that, we argue, potentially allow tort to address historical injustice. These building blocks were illustrated through previous landmark cases of systemic and historical injustice, including the Rawagede, Srebrenica, Birthmothers, and Shell cases. The article thus argued that, despite the limitations, these can be particularly powerful for the case of the slavery justice movement. Tort cases on slavery have the potential to build upon an already strong public, political, and academic conversation – even where the eventual outcome of the tort case might not be in line with its initial claims.

Transformative justice and civil recourse together show how tort can challenge lawyers and judges to seek rapprochement with plaintiffs’ lived realities of harm. In this process, they can question social norms and even help establish new ones. Especially in cases where powerful institutions such as multinationals, religious organisations, and most notably the state are the defendants, there is a possibility for transformation. This is: when judges are able to use the remedies at their disposal – and the institution seizes an opportunity to establish itself as a moral and responsible actor, by revisiting social norms and accepting the plaintiffs’ critique on its institutional power. Law and rights, after all, have the potential to make both the structural injustices of the past and the contours of a just society visible. Courts can be places to challenge these power structures. This is highly relevant for the slavery injustice movement.

Of course, it is nowhere a given that this potential turns into success. But with the increasing momentum of systemic and historical injustice tort litigation that we see in practice, we may find ourselves currently at a crossroad. It is to see whether and in what ways lawyers and judges might take this leap and adopt a ‘more responsive or activist attitude’120x Loth, ‘Is Tort Law a Remedy for Historical Injustice?’, 18. (re)discovering the potential that tort carries. The impending tort cases for the Dutch slavery justice movement will, without doubt, show us whether and in what ways this momentum, potential, and aspiration can indeed manifest itself.

- * The authors would like to thank the reviewer and editors for their great suggestions. The findings and ideas presented in this article have benefitted from the work of our colleagues in our Dialogics of Justice-research team: Obiozo Ukpabi, Marrit Woudwijk, Naomi Ormskerk, and Luna Bonvie.

-

1 Citation (close to literal) and translation on the basis of notes taken by authors from the livestream of the court case of the District Court The Hague on 24 September 2021. See also District Court The Hague, 26 January 2022 (Afstandsmoeders), ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2022:432.

-

2 The Dutch word afstandsmoeders reflects the facts that these women had to ‘hand over’ (Dutch: afstand doen van) their children. The word, however, also carries the meaning of ‘distance’ (Dutch: afstand). The English translation cannot do justice to this subtlety and normativity. We use the English translation that is most common in international media coverage of the case.

-

3 The International Criminal Court (ICC) is plagued by slowness, disappointing results in light of enormous costs, a striking North-South bias – experienced as ‘colonial violence’ – see Kamari M. Clarke, Affective Justice. The International Criminal Court and the Pan-Africanist Pushback (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2019) – and its Trust Fund for Victims that grants victims the rights to seek and receive reparations has for a long time been chronically underfunded, see Jo-Anne Wemmers, ‘Special Issue on Victim Reparation and the International Criminal Court’, The International Review of Victimology 16/2 (2009).

-

4 See Michael R. Marrus, Some Measure of Justice. The Holocaust Era Restitution Campaign of the 1990s (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009); Berber Bevernage, ‘Cleaning Up the Mess of Empire? Evidence, Time and Memory in “Historic Justice” Cases Concerning the Former British Empire (2000-Present)’, Storia della Storiografia/History of Historiography 76/2 (2019); Marc Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?: On Slavery Reparations, Post-Colonial Redress, and the Legitimations of Tort Law’, Journal of European Tort Law 11/3 (2020): 181-207; Caroline Elkins, ‘History on Trial. Mau Mau Reparations and the High Court of Justice’, in Time for Reparations. A Global Perspective, eds. Jacqueline Bhabha et al. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 101-118.

-

5 Bevernage, ‘Cleaning Up the Mess of Empire?’, 63.

-

6 Cedric Ryngaert, ‘Tort Litigation in Respect of Overseas Violations of Environmental Law Committed by Corporations: Lessons from the Akpan v. Shell Litigation in the Netherlands’, McGill International Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy 8/2 (2012): 245-260; Cedric Ryngaert and Kushtrim Istrefi, ‘Introduction Special Issue “The Legacy of the Mothers of Srebrenica Case”‘, Utrecht Journal of International and European Law 36/2 (2021): 114-117; Larissa van den Herik, ‘Addressing “Colonial Crimes” through Reparations? Adjudicating Dutch Atrocities Committed in Indonesia’, Journal of International Criminal Justice 10/3 (2012): 693-705; Nicole Immler, ‘Human Rights as a Secular Imaginary in the Field of Transitional Justice. The Dutch-Indonesian “Rawagede Case”‘, in Social Imaginaries in a Globalizing World, eds. Hans Alma and Guido Vanheeswijk (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 193-222; Nicole Immler, ‘Colonial history at court: Legal decisions and their dilemmas’, in Time for Reparations. A Global Perspective, eds. Jacqueline Bhabha et al. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 153-167.

-

7 Makau Mutua, ‘Reparations for Slavery: A Productive Strategy?’, in Time for Reparations. A Global Perspective, eds. Jacqueline Bhabha et al. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), 32.

-

8 The statute of limitations, meant to prevent potential defendants from unfair trials about long-past harm, from which they cannot reasonably be expected to defend themselves – prevents parties from bringing harm to court that has been committed in the far-away past. However, when the plaintiffs can prove that, for example, they were not aware of the harm until a more recent point in time, the statute of limitations does not apply. The specifics of this case will be elaborated on later in this article.

-

9 Wouter Veraart, ‘Uitzondering of precedent? De historische dubbelzinnigheid van de Rawagede-uitspraak’, Ars Aequi 4 (2012): 251-259.

-

10 Van den Herik, ‘Addressing ‘Colonial Crimes’ through Reparations?’, 2.

-

11 Bart Luttikhuis, ‘Juridisch afgedwongen excuses. Rawagedeh, Zuid-Celebes en de Nederlandse terughoudendheid’, BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 129/4 (2014): 92-105; Chris Lorenz, ‘Can a Criminal Event in the Past Disappear in a Garbage Bin in the Present? Dutch Colonial Memory and Human Rights: The Case of Rawagede’, in Afterlife of Events: Perspectives on Mnemohistory, ed. Marek Tamm (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 219-241.

-

12 Immler, ‘Human Rights as a Secular Imaginary in the Field of Transitional Justice’, 218.

-

13 Kaimipomo D. Wenger, ‘Forty Acres and a lawsuit: legal claims for reparations’, Race, Ethnicity and Law. Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance 22 (2017): 89. See also Hanoch Dagan, ‘Restitution and Slavery: On Incomplete Commodification, Intergenerational Justice, and Legal Transition’, Boston University Law Review 84/5 (2004): 1142.

-

14 For more critique on the ability of tort to address historical injustice cases, see Joel Levin, Tort Wars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 124, 126, 136, 153.

-

15 See Kaimipono D. Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery; or, Why the Master’s Mules Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House’, in Injury and Injustice. The Cultural Politics of Harm and Redress, eds. Anne Bloom et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 257-258. Wenger reflects here the conventional thinking on the topic; but he holds that tort law is equipped and capable of dealing with such large cases of harm – and strongly endorses the use of tort and other justice avenues for historical injustice cases (at 256).

-

16 Sally E. Merry, ‘Foreword’, in Mark Goodale, Anthropology and Law. A Critical Introduction (New York: New York University Press, 2017), ix-xv at xii; Carl Auerbach, ‘Legal Tasks for the Sociologist’, Law & Society Review 1/1 (1966): 96.

-

17 Richard L. Abel, ‘Law and Society: Project and Practice’, Annual Review of Law and Social Science 6 (2010): 19.

-

18 Michael McCann, David M. Engel and Anne Bloom, ‘Introduction’, in Injury and Injustice. The Cultural Politics of Harm and Redress, eds. Anne Bloom et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 1.

-

19 Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery’, 260.

-

20 McCann, Engel and Bloom, ‘Introduction’, 8, 12.

-

21 McCann, Engel and Bloom, ‘Introduction’, 1, 22.

-

22 Martha Minow, ‘Forgiveness, Law, and Justice’, Calif. L. Rev. 103 (2015): 1619.

-

23 Janine Ubink and Sindiso Mnisi, ‘Courting Custom. Regulating Access to Justice in Rural South Africa and Malawi’, Law & Society Review 51/4 (2017): 830.

-

24 Tsachi Keren-Paz, Torts, Egalitarianism and Distributive Justice (Hampshire: Ashgate, 2007), 17.

-

25 As compared with instrumentalist and economic readings of tort law that were dominant up until recently.

-

26 Anita Bernstein, ‘Distributive Justice through Tort (and Why Sociolegal Scholars Should Care)’, Law & Social Inquiry 35/4 (2010): 1099-1135; Keren-Paz, Torts, Egalitarianism and Distributive Justice.

-

27 Benjamin Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’, Georgetown Law Journal 91/3 (2003): 695-756.

-

28 Alberto Pino-Emhart, ‘Apologies and Damages: The Moral Demands of Tort Law as a Reparative Mechanism’, (PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2015); Rahul Kumar, ‘Why Reparations?’, in Philosophical Foundations of the Law of Torts, ed. John Oberdiek (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 193-213.

-

29 Loth, ‘How Does Tort Law Deal with Historical Injustice?’; Pino-Emhart, ‘Apologies and Damages’; Keren-Paz, Torts, Egalitarianism and Distributive Justice, 17.

-

30 Zipursky, ‘Civil Recourse, Not Corrective Justice’.

-

31 Arie Freiberg and Pat O’Malley, ‘State Intervention and the Civil Offense’, Law & Society Review 18/3 (1984): 388.

-

32 Lisa Laplante, ‘Just Repair’, Cornell International Law Journal 48/3 (2015): 513.

-

33 Nicole Immler, ‘What is Meant by “Repair” when Claiming Reparations for Colonial Wrongs? Transformative Justice for the Dutch Slavery Past’, Slaveries & Post-Slaveries 5 (2025), 22.

-

34 Alma Mustafić and Niké Wentholt, ‘Finding the Facts but Ending the Conversation?’, Netherlands Yearbook of International Law (forthcoming).

-

35 Arthur Ripstein, ‘Civil Recourse and Separation of Wrongs and Remedies’, Florida State University Law Review 39/1 (2011): 171.

-

36 Minow, ‘Forgiveness, Law, and Justice’, 1627.

-

37 Goodale, Anthropology and Law, 22.

-

38 Goodale, Anthropology and Law, 22.

-

39 Wenger, ‘The Unconscionable Impossibility of Reparations for Slavery’.

-

40 Stiina Löytömäki, ‘The Law and Collective Memory of Colonialism: France and the Case of “belated” Transitional Justice’, International Journal of Transitional Justice 7/2 (2013): 221.

-

41 Mari Matsuda, ‘Looking to the Bottom: Critical Legal Studies and Reparations’, Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 1 (1987): 324-397; Goodale, Anthropology and Law; Merry, ‘Foreword’.

-